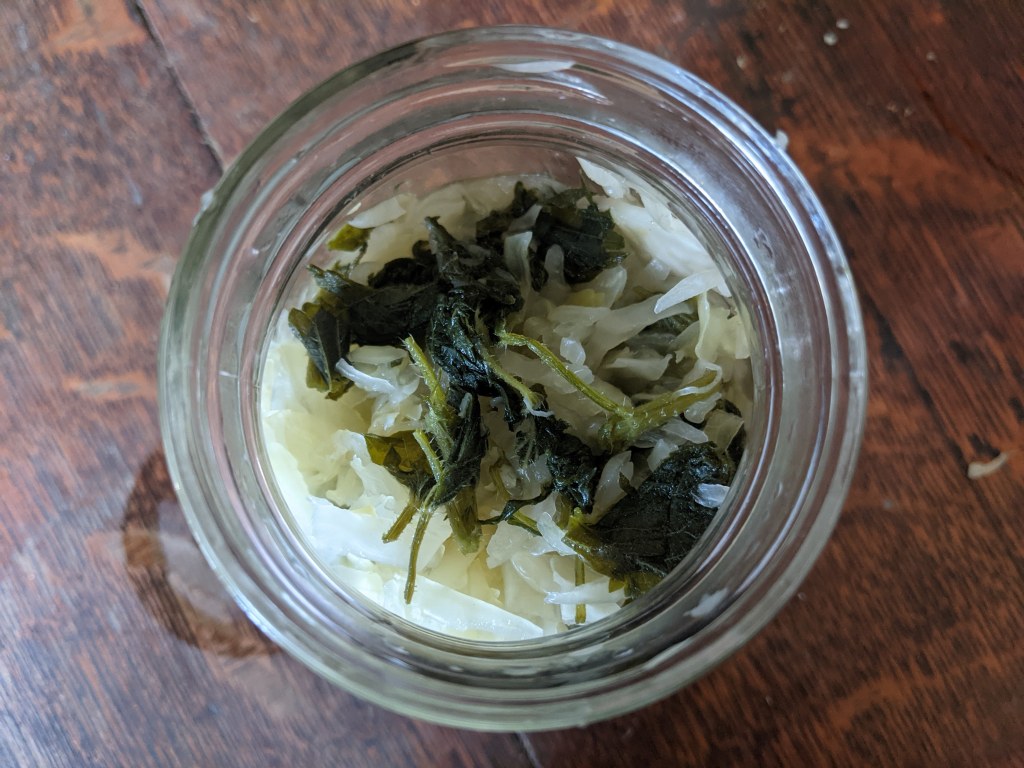

Fermented hot sauce can be a complicated or quite simple affair, but is indisputably indispensable for bringing your winter stored potatoes, squash, and beans to life. My preferred method is just pureeing hot peppers with a little salt, letting it ferment, and donezo! That works well with fresh peppers but you can also ferment them submerged in a salt brine if they’re dried. Though if you want to take your fermented peppers one step further, try making fermented hot pepper flakes from your fermented hot sauce.

It’s a pretty open door as to how you might want to get creative with making your fermented hot sauce. Add a clove of garlic (or maybe roasted garlic) to your puree, or a hunk of onion, perhaps some garden herbs like oregano. Follow you gardens and markets.

A great little trick is fermented hot pepper flakes. These pepper flakes are a fun addition to a pantry, sneaking a hot and tangy zing to your foods, and super easy to do, while stretching one product into two. Instructions are below, just be sure to do your drying outside if possible or where there’s good ventilation!

Fermented Hot Sauce Method

1. Clean and destem your choice of fresh hot pepper or hot pepper medley. Prepare any other ingrdients: garlic, onion, fruit, herbs, etc.

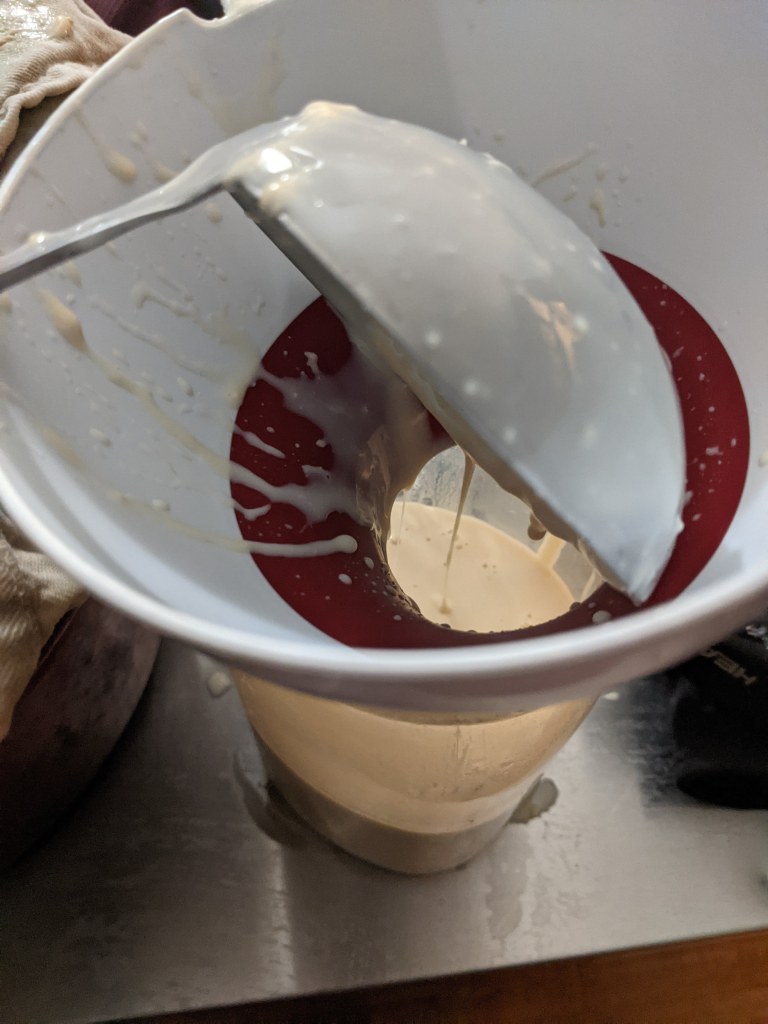

2. Grind everything together in a food processor or blender. Add a bits of water as necessary to get a fully purred slurry to a nice slushy consistency.

3. Stir in salt for a 3% brine, so that’s about 1-3 tablespoons per a quart of slurry.

4. Ferment with lid on or off according to preference. I like to do the lid on and burp it every few days to keep the weird films from developing on the surface. Without a lid make sure to stir it up every few days.

5. Ferment to your preference, maybe 1 week, maybe a few months. Pack it away in the fridge to store when or cap it at room temperature with a snug twist sealing lid.

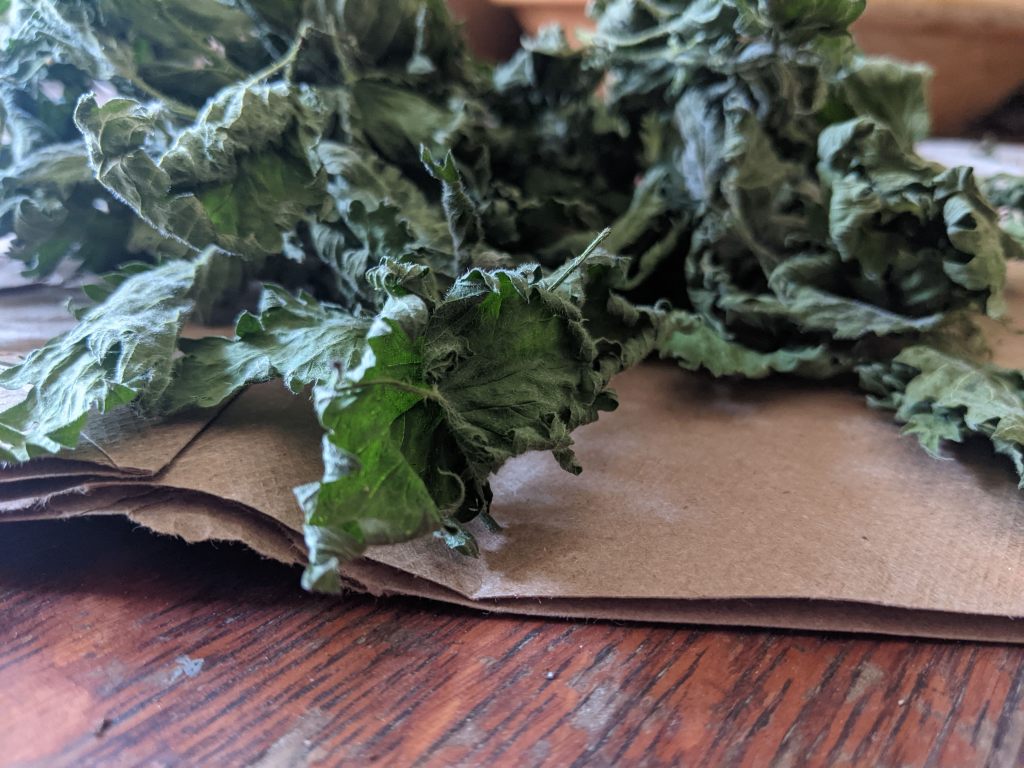

Fermented Hot Pepper Flakes

- After your hot sauce is done fermenting strain out the solids using a fine mesh strainer.

- Bottle up your hot sauce liquid, then dehydrate the solids using your favorite method. If you don’t have a dehydrator you can dry it with a regular old fan or in the oven at the lowest setting. (The oven will require some close monitoring and frequent stirring. A fan might be better done outside.)

3. Be sure to break up the fermented solids every so often when dehydrating as they will clump together. Also be careful as the drying fumes could be intense!

4. Grind up the dried solids or break up with your hands and store away!

*Most of these posts are resources for Ferment Pittsburgh’s monthly newsletter that features seasonal ideas, techniques, and musings. Consider jumping aboard?